Greed (game show)

| Greed | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Game show |

| Created by | |

| Written by | Eric Peterkofsky Joseph Kaufmann III Hilary Schacter Mandel Ilagan Bob Boden Jeffrey Mirkin |

| Directed by |

|

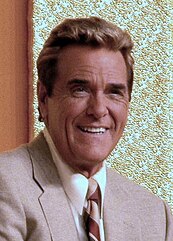

| Presented by | Chuck Woolery |

| Announcer | Mark Thompson |

| Composer | Edgar Struble |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 1 |

| No. of episodes | 44 |

| Production | |

| Executive producers |

|

| Production location | Los Angeles |

| Editor | Floyd Ingram |

| Running time | 42–44 minutes |

| Production company | Dick Clark Productions |

| Original release | |

| Network | Fox |

| Release | November 4, 1999 – July 14, 2000 |

Greed[a] is an American television game show that aired on Fox for one season. Chuck Woolery was the show's host while Mark Thompson was its announcer. The series format consisted of a team of contestants who answered a set of up to eight multiple-choice questions (the first set of four containing one right answer and the second set of four containing four right answers) for a potential prize of up to $2,000,000[b] (equivalent to $3,658,000 in 2023).

Dick Clark and Bob Boden of Dick Clark Productions created the series in response to the success of ABC's Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Production was rushed in an effort to launch the show before Millionaire's new season, and the show premiered less than two months after it was initially pitched. A pilot episode was omitted, and Fox aired its first episode of Greed on November 4, 1999.

While its Nielsen ratings were not quite as successful as Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, Greed still improved on Fox's performance year-to-year in its timeslots. The show's critical reception was mixed; some critics saw it as a rip-off of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, while others believed Greed was the more intriguing and dramatic of the two programs. Its final episode aired July 14, 2000, and Greed was abruptly canceled following the conclusion of its first season as Fox's leadership shifted the network's focus to scripted programming. The top prize was never awarded; only one contestant advanced to the eighth and final question, failing to win the prize.

Gameplay

[edit]Qualifying round

[edit]Six contestants are asked a question with a numerical answer. After all six submit a number, the answer is revealed and the contestant whose numerical guess is farthest from the exact answer is eliminated.[4] The remaining contestants are stationed at podiums based upon the proximity of their guess to the correct answer, and the contestant who had the closest guess becomes the team's captain. If two or more contestants give the same guess or guesses that are of equal distance from the correct answer, the one who locks in their answer before the other(s) receives the higher ranking.[5]

Question round

[edit]The team attempts to answer a series of eight questions worth successively higher amounts, from $25,000 up to $2,000,000. Each of the first four questions has one correct answer to be chosen from several options (four for questions one and two, five for questions three and four).[5] The host reads the question and possible answers to one contestant, who has unlimited time to select one of them. The captain can either accept that answer or replace it with a different one.[6] If the final choice is correct, the team's winnings are increased to the value of that question; the captain can then choose to either quit the game or risk the money on the next question.[6] If the captain quits after any of these four questions, the money is split evenly among all five team members. Giving or accepting a wrong answer ends the game and forfeits all winnings. The team member in the lowest position (farthest from the correct answer when a qualifying question was played) gives the answer to the first question, and each question after that is answered by the member in the next higher position.[6]

The remaining four questions each have four correct answers to be chosen from several options, starting with six for question five and increasing by one for each question after that.[7] The host reveals the category of the upcoming fifth question to the captain and offers a chance to end the game, with the prize money being divided among the remaining players according to their shares. If the captain chooses to continue, a "Terminator" round is played prior to the question being asked. The captain is given a single "Freebie" lifeline prior to question five and can use it once to eliminate a wrong answer from a question.[8]

For questions five through seven, answers are given one at a time by the remaining contestants with the captain answering last, then (if necessary) choosing to either give enough additional answers to make four or delegate the choices to other members. Once all the answers are in, the captain may either approve the choices as they stand or change one of them if desired.[9] Answers are revealed individually as correct or incorrect; if three correct answers are found, the host offers a buyout to quit the game.[8] Ten percent of the question value is offered on questions five and six ($20,000 and $50,000 respectively), to be split evenly among the remaining players, and the team's decision is entirely up to the captain.[10] On question seven, each team member can choose to take an individual buyout consisting of a luxury automobile and $25,000 cash (approximately $100,000 total value).[11][c]

If the captain (at questions five and six) or at least one team member (at question seven) chooses to continue with the game, the fourth answer is revealed. If it is correct, the team splits the cash award for the question at that level. If an incorrect answer is revealed at any point, the game ends and the team leaves with nothing.[13]

| Question | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Greed[14] | Super Greed[15] | |

| 8 | $2,000,000 | $4,000,000 |

| 7 | $1,000,000 | $2,000,000 |

| 6 | $500,000 | $1,000,000 |

| 5 | $200,000 | |

| 4 | $100,000 | |

| 3 | $75,000 | |

| 2 | $50,000 | |

| 1 | $25,000 | |

Terminator

[edit]A Terminator challenge is played before each question starting at question five. One contestant is chosen at random and given the option to challenge a teammate (including the team captain) to a one-question showdown for their share of the team's collective winnings. If the selected contestant issues a challenge, they are given a guaranteed $10,000 in cash to keep regardless of the result of the outcome of the Terminator or the overall game.[16] If the selected contestant does not wish to issue a challenge, the team remains as it was and the host proceeds to the next question.[12]

The two contestants face each other across podiums at center stage, and the host reads a toss-up question with a single answer. The first contestant to buzz in and answer correctly eliminates the other contestant from the game and claims their share of the collective winnings.[6] If a contestant buzzes in and provides an incorrect response or does not immediately respond, their opponent wins by default.[12] If the team captain is eliminated, the contestant who wins the challenge becomes the new captain.[17]

$2,000,000 question

[edit]Before the $2,000,000 question, each team member can decide to quit with their share of the team's collective winnings or continue playing. If any team members choose to continue, a question with nine possible answers is presented, of which four are correct.[18] Contestants who reach this level are given 30 seconds to select four answers. If they fail to do so within the time limit, the game ends and they leave with nothing.[19] Following the selection of answers, correct responses are revealed individually. None of the answers can be changed and no buyout is offered following the reveal of the third correct answer. If all four chosen answers are correct, the contestant (or team) wins $2,000,000.[18]

Only one contestant played the final question throughout the show's run.[20] On the episode that aired on November 18, 1999, Daniel Avila chose to risk his $200,000 individual winnings to play for the top prize (which had been increased to $2,200,000 as it was during Greed's progressive jackpot shows).[21][22] However, Avila missed the question based on a Yale University study about the four smells most recognizable to the human nose (peanut butter, coffee, Vicks VapoRub, and chocolate). Avila correctly guessed peanut butter, coffee, and Vicks VapoRub but incorrectly guessed tuna instead of chocolate, and left with nothing.[19]

Rule changes

[edit]Top prize

[edit]For the first six episodes of Greed's run, aired November 4, 1999, until December 2, 1999, the top prize started at $2,000,000 and increased by $50,000 after every game in which it went unclaimed.[21] As no team had reached the jackpot question and provided the necessary correct answers, the jackpot reached $2,550,000 in the first month.[3] When the program was picked up as a regular series in Fox's weekly lineup, the top prize was changed to a flat $2,000,000.[21]

Greed: Million Dollar Moment

[edit]In February 2000, eight previous Greed contestants were brought back for a "Million Dollar Moment" at the end of each of four episodes. The contestants were all players who had gotten close to the $2,000,000 jackpot question. Two contestants faced off with a Terminator-style sudden-death question, and the winner was given a $1,000,000 question with eight possible choices. The contestant had up to 30 seconds to study the question, then 10 seconds to lock in the four correct answers to win the money. Correct answers were revealed one at a time (as on the jackpot question, no buyout was offered after the third correct answer), and if all four were correct, the contestant won an additional $1,000,000.[23]

Curtis Warren became Greed's only Million Dollar Moment winner when he successfully answered a question about movies based on television shows on the episode that aired on February 11, 2000.[24] Warren was the program's biggest winner with $1,410,000[25] and briefly held the title of biggest U.S. game show winner in history;[23] combined with an earlier six-figure winning streak on Sale of the Century in 1986 and an appearance on Win Ben Stein's Money, his total game show winnings stood at $1,546,988.[26] Warren's record was broken shortly thereafter by David Legler,[25] who won $1,765,000 on Twenty-One.[27][28] He has since been surpassed by others, including Jeopardy! champions Ken Jennings, Brad Rutter, and James Holzhauer.[29]

Super Greed

[edit]From April 28 to May 19, 2000, the show was known as Super Greed.[30] The qualifying question was eliminated, and the values for the top three questions were doubled, making the eighth question worth a potential $4,000,000. The cash buyout on the sixth question ($1,000,000) was increased to $100,000, and any team that got this question right and continued past it was guaranteed a separate $200,000 regardless of the outcome of the game.[15] During this period, Phyllis Harris served as captain of a team that answered seven questions correctly and shared a $2,000,000 prize, though she and her teammates elected to leave the game before attempting the final $4,000,000 question.[31]

Production

[edit]Greed was created by Dick Clark and Bob Boden of Dick Clark Productions.[32] An hour-long program,[33] it was considered by television critics and network producers to be Fox's response to ABC's Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,[34][35] while Fox executive Mike Darnell later confirmed that Fox was "inspired by the success of Millionaire."[36] Boden had initially pitched a similar format that he called All for One to NBC, but the network passed on the idea as they already had a revival of Twenty-One in development.[21] Clark, meanwhile, wanted a more "provocative" title; when Boden told Clark "the core of the show is greed," Clark responded, "Let's just call it Greed."[21]

Clark and Boden pitched the show to Fox in September, and six episodes were ordered, which began taping less than three weeks later.[37] The series was only given about a month of preparation before it was set to premiere in November 1999.[38] Fox had set the target premiere date of November 4, because it was three days before Millionaire was set to return to ABC, and by mid-October, one Fox executive was concerned the network might not have the show ready in time.[39]

Producers considered many potential hosts in the selection process, including veteran game show hosts Chuck Woolery and Bob Eubanks, as well as Keith Olbermann and Gordon Elliott.[37] On October 13, The Philadelphia Inquirer's Gail Shister reported that Olbermann was close to being named host, while also noting Phil Donahue was Fox's first choice, though he proved to be too expensive for the network.[40] Woolery was ultimately selected as the show's host due to his game show experience.[37] The production team omitted taping a pilot,[37] allowing the series to be ready in time for its premiere on November 4.[41] Mark Thompson served as the announcer,[42] Bob Levy and Chris Donovan directed the program,[43] and Edgar Struble composed the soundtrack.[44] It was initially subtitled "Greed: The Multi-Million Dollar Challenge".[41][45] The tagline for the series was "the Richest, Most Dangerous Game in America."[46] In January 2000, Fox brought Greed back to its schedule by airing it three nights in a row before it began airing weekly on Fridays,[47] in order to avoid competing head-to-head with Millionaire on Thursdays.[48]

The majority of Greed's contestants during its first couple of months were hand-picked and recruited by the show's producers after a multiple-choice qualification test.[49] Many of them had already appeared on other trivia-based game shows,[50] including Avila and Warren, who were previously winning contestants on Jeopardy![51] and Win Ben Stein's Money respectively.[52] The window between Avila's test and when his episode taped was only three days, as he took the test on a Saturday and taped the show the following Tuesday.[53] Once the show became a regular series, Fox began a more nationwide search for contestants, and any legal resident of the U.S. was invited to call or mail in an entry for a chance to audition.[53] Some travel and accommodations were provided by Priceline.com.[5]

Like Millionaire, Greed's basic set was atypical of the traditional game show, giving the show a more dramatic feel.[54] The New York Times' Julia Chaplin compared the set to a video game, saying it was "painted to look like stone blocks, reminiscent of the torch-lighted medieval castles in games like Doom and Soul Calibur."[54] Greed's set designer, Jimmy Cuomo, noted the inspiration from science fiction in his set, specifically from Star Trek and various castle settings in video games.[54]

Fox abruptly canceled the program on July 14, 2000.[43][55] By 2001, Fox executives Sandy Grushow and Gail Berman had led a shift in the network's focus through a greater emphasis on scripted programming.[56] In December 2000, Clark stated that he was working on a revised version of Greed that he would initially pitch to Fox and then propose to other networks.[57] While this proposed revival was never launched, Greed's original 44-episode run was acquired by Game Show Network (GSN) for reruns in January 2002.[58]

International versions

[edit]

Following Greed's success in the United States, the show was adapted and recreated in several other countries as a worldwide franchise. American talk show host Jerry Springer hosted a British adaptation of the series on Channel 5 in 2001.[59][60] Other versions of Greed have existed in Argentina,[61] Australia,[62] Denmark,[63] Finland,[64] France,[65] Germany,[66] Israel,[67] Italy,[68] Lebanon,[69] Poland,[70] Portugal,[71] Russia,[72] South Africa,[73] Spain,[74] Sweden,[75] Turkey,[76] and Venezuela.[77] Additionally, the original American series aired in Canada on Global.[78]

Reception

[edit]Greed received mixed critiques. At the beginning of the show's run, some critics saw Greed as little more than a bad attempt to capitalize on ABC's success with Millionaire.[79] Scott D. Pierce of Deseret News called the series "a rip-off" of Millionaire, adding "just how liberally Fox and Dick Clark Productions stole from the ABC hit is a bit of a shocker".[80] Dana Gee of The Province wrote "Greed fails to entertain" while also criticizing the difficulty of the questions.[81] Joyce Millman of Salon added, "a stench of desperation surrounds the show" and referred to it as "Fox's last hope" for a primetime hit that television season.[82] Millionaire host Regis Philbin was unsurprised Fox launched a competing show, saying, "It's so Fox, isn't it?"[83] In comparing Greed to Millionaire, New York Daily News's David Bianculli wrote that the former "doesn't have heart" as it allowed contestants to duel with each other, while also arguing Woolery lacked "warmth and empathy" as host compared to Philbin on Millionaire.[84] Joanne Weintraub of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel called Greed "a glum affair" and added that the show seemed "more tedious than tense."[85] Alan Pergament of The Buffalo News shared the sentiment that Greed was little more than a Millionaire rip-off, though he conceded its Nielsen ratings "were good by Fox standards."[86]

Others were more favorable of Greed, particularly due to its elements of drama. Writing for The New York Times two weeks after the show's debut, Caryn James believed Greed was a more dramatic show than Millionaire, comparing it to "blood sport" and saying it "evokes uglier sentiments and brings in less conventional contestants".[87] Time's James Poniewozik gave the series a more positive review, arguing that "Greed Trumps Millionaire" based on its lack of lifelines and ability to pit teammates against each other.[88] In December, United Media columnist Kevin McDonough stated that he also preferred Greed over the ABC game show,[89] while Bill Carter (also of The New York Times) wrote that the series "has fared passably well".[90]

Jeopardy! champion Bob Harris, who won $200,000 on an episode of Super Greed, compared the two trivia-based game shows in his 2006 book Prisoner of Trebekistan, saying, "If Jeopardy! was a relationship, Greed was a tawdry affair: quick, flashy, loud, and kind of confusing."[91] Harris also recalled a conversation with Woolery years later where the Greed host himself admitted that the show's rules were "complicated."[91] In 2019, Forbes's Marc Berman wrote an article titled "20 Years Later: I Still Feel The Need For Greed", arguing that the show could eventually be rebooted due to the "current era of [game show] revivals".[92]

Ratings

[edit]Greed premiered with a 4.0 rating in adults 18–49[93] and a total of 9.9 million viewers,[94] improving on Fox's Thursday night performance from its other shows that season.[95][93] The rating gave Fox an improvement of more than 100 percent in that time slot over the previous week, marking the network's best Thursday ratings in more than six months.[38] By mid-January 2000, Greed brought in around 12 million viewers, which marked Fox's best performance in the time slot since the debut of Millennium,[96] although the number totaled less than half of Millionaire's audience of more than 28 million.[97] Alan Johnson of the Chicago Tribune wrote that Greed's producers would occasionally have to displace the show and change its schedule to avoid going head-to-head against Millionaire.[98] The July 14, 2000, episode (which would ultimately be the series finale) earned 6.7 million viewers.[99]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The show's full title was Greed: The Series as reflected in its title card and occasionally in print media.[1][2]

- ^ The top prize was temporarily raised during the first several episodes to as high as $2,550,000 as part of a progressive jackpot.[3]

- ^ The total value referenced reflects the value at the time of the show's release in 1999.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Greed. Season 1. Episode 7. December 9, 1999. Fox.

- ^ Wertheimer, Ron (January 14, 2000). "The next quiz: How long can the quiz shows last?". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Greed. Season 1. Episode 6. December 2, 1999. Fox.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c Greed. Season 1. Episode 2. November 4, 1999. Fox.

- ^ a b c d Furman & Furman 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Furman & Furman 2000, p. 40.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Greed. Season 1. Episode 3. November 11, 1999. Fox.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 37.

- ^ "'Beyond the Prairie'". The Washington Post. January 2, 2000. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

The remaining five players together attempt to climb the "Tower of Greed" ($25,000 to $50,000 to $75,000 to $100,000 to $200,000 to $500,000 to $1 million to $2 million or more).

- ^ a b "Super Greed". Greed. Season 1. Episode 32. April 28, 2000. Fox.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 38.

- ^ "Super Greed". Greed. Season 1. Episode 33. May 2, 2000. Fox.

- ^ a b Furman & Furman 2000, p. 42.

- ^ a b Furman & Furman 2000, p. 43.

- ^ DeMichael 2009, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e Nedeff 2018, pp. 306.

- ^ Greed. Season 1. Episode 4. November 18, 1999. Fox.

- ^ a b Greed. Season 1. Episode 17. February 11, 2000. Fox.

- ^ Donlan, Francesca (February 20, 2000). "Wanna be a millionaire? Players get chance to give final answers". The Desert Sun. Palm Springs, California. p. 57. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Taylor, Jonathan (September 6, 2004). "He'll take 'game show champs' for $1.3 million". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 49. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Slenske, Michael (January 2005). "Trivial Pursuits". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Bentley, Rick (April 9, 2000). "How to Get on a Game Show". The Fresno Bee. Fresno, California. McClatchy. p. 81. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Davis, Laurie B. (March 2, 2000). "Education comes first for M.B.A. student who won $1.7 million". University of Chicago Chronicle. 19 (11). Archived from the original on November 1, 2003. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ^ "Contestant Zone: Jeopardy! Hall of Fame". Jeopardy.com. Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "Fox to Air Five Special Super Greed Editions". Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. Gannett. April 28, 2000. p. 57. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Come On Down". Las Vegas Sun. January 22, 2001. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Petrozzello, Donna. "The answer for TV networks: quiz shows". The Greenville News. Greenville, South Carolina. p. 32. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (October 17, 1999). "TV Revives the Darndest Things". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (November 5, 1999). "Want to Be a Millionaire?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Goodykoontz, Bill (November 7, 1999). "Fox game show pits team spirit vs. Greed". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. p. 191. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Jefferson, Graham (November 4, 1999). "Fox's Greed met the challenge". USA Today. Gannett. p. D, 3:1. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Carter, Bill (November 14, 1999). "A Million Reasons The TV Quiz Show Has Struck It Rich". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (October 15, 1999). "On Retainer: CBS Law Shows Will Be Back". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Shister, Gail (October 13, 1999). "Rematch with cancer fails to shake Today chief's confidence". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 44. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Greed: Turn on Your Teammates". The Washington Post. October 31, 1999. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Terrace 2009, p. 613.

- ^ a b DeMichael 2009, p. 158.

- ^ "Edgar Struble and Friends to perform at West Shore". Mason County Press. November 26, 2013. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

His recent composing credits include Dick Clark's Your Big Break and Greed series...

- ^ Rosenberg, Howard (November 10, 1999). "If This Is the Answer, What's the Question?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Wertheimer, Ron (January 11, 2000). "Critic's Notebook; An Overdose Of Quizzes? No Question". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

Greed ... bills itself as 'the richest, most dangerous game in America.'

- ^ "Millionaire First Out of the Gate". Chicago Tribune. December 31, 1999. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (December 29, 1999). "At Fox TV, a Hot Spot for a Hotshot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Furman & Furman 2000, p. 47.

- ^ "Show No. 1525 (Richard Dial vs. Bennett Crocker vs. Dan Avila)". Jeopardy!. Season 7. March 29, 1991. Syndicated.

- ^ Win Ben Stein's Money. Season 2. Episode 7. August 4, 1998. Comedy Central.

- ^ a b Furman & Furman 2000, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Chaplin, Julia (January 16, 2000). "Quiz Shows Make Every Contestant A Video Gladiator". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Baber 2008, p. 274.

- ^ Kronke, David; Kuklenski, Valerie (July 19, 2001). "Fox touts fiction but succumbs to reality". The York Dispatch. Pasedena, California. Los Angeles Daily News. p. 25. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bobbin, Jay (December 31, 2000). "What happened to NBC's Daddio and ..." Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Game Show Network gets Greed -y". The Post-Star. Los Angeles, California. Zap2it. January 19, 2002. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Wells, Matt (March 8, 2001). "Channel 5 lines up Jerry Springer for game show with £1m prize". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "Greed grips Channel 5". BBC News. BBC. March 8, 2001. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Audacia, todos los días de competencia" [Audacity, every day of competition] (PDF). Diario Hoy (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Bonner 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Henriksen, John (August 14, 2001). "Grisk når det gælder" [Greedy when it comes]. Dagbladet Information (in Danish). A/S Information. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Greed" (in Finnish). MTV3.fi. Archived from the original on February 19, 2003. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ "Mission : 1 million – Emissions TV" (in French). Toutelatele.com. November 4, 2002. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "CA$H – Das eine Million Mark-Quiz" [CA$H – The One Million Mark Quiz]. grundy-le.net (in German). Archived from the original on February 22, 2013.

- ^ ובתפקיד ארז טל –- אברי גלעד [And in the role of Erez Tal – Avri Gilad]. Walla! (in Hebrew). October 3, 2000. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Greed con Barbareschi promosso in prima serata" [Greed with Barbareschi promoted in prime time]. la Repubblica (in Italian). October 29, 2000. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ برامج المسابقات انتشرت بسرعة مثل "الجمرة الخبيثة" وضاعت بين عسل المعلومات وعلقم المال [Competition programs spread quickly as "anthrax" and were lost between the honey of information and the money bag]. Asharq Al-Awsat (in Arabic). December 14, 2001. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Dzienny, Serwis (April 25, 2001). "Polsat Stawia Na Chciwych Zawodników" [Polsat focuses on the greedy players]. mmp24.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Carlos Cruz leva "Febre do Dinheiro" à SIC" [Carlos Cruz takes "Money Fever" to SIC]. Tsf.pt (in Portuguese). July 6, 2000. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Программу "Алчность" на НТВ будут вести Игорь Янковский и Альфред Кох [Program "Greed" on NTV will be hosted by Igor Yankovsky and Alfred Kokh] (in Russian). Newsru.com. September 5, 2001. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Pearson, Brian (September 26, 2000). "Games and reality strong in South Africa". Variety. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Alcaide, Soledad (October 20, 2000). "El concurso de TVE 'Audacia' entregó 5 millones en su estreno" [The TVE contest 'Audacia' delivered 5 million in its premiere]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Tittarna svek nya "Vinna eller försvinna"" [Viewers betray new "Win or disappear"]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). February 6, 2001. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Atv'den 5 büyük bomba" [5 big bombs from ATV]. Sabah (in Turkish). September 3, 2000. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ "Una contagiosa Fiebre de Dinero" [A contagious Money Rush] (in Spanish). Noticiero Venevision. May 29, 2001. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011.

- ^ Zerbisias, Antonia (November 4, 1999). "The $$$ game show rush; U.S. networks scramble to cash in with big bucks". Toronto Star. Toronto, Ontario. p. A37. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (January 12, 2002). "Shocking Behavior: ABC and Fox Sue Over Reality Shows". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Pierce, Scott D. (November 10, 1999). "Fox's Greed is a Blatant Rip-Off: Show Steals from 'Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?'". Deseret News. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Gee, Dana (November 7, 1999). "Greed fails to entertain". The Province. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. p. 101. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Millman, Joyce (November 16, 1999). "For the Love of the Game Show". Salon. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Span, Paula (November 8, 1999). "ABC's Million-Dollar Maybe". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Bianculli, David (November 9, 1999). "They'd sell their own mothers on Greed". Dayton Daily News. Dayton, Ohio. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weintraub, Joanne (November 7, 1999). "Greed good? No, rather tiresome". Lancaster Eagle-Gazette. Lancaster, Ohio. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. p. 20. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pergament, Alan (November 9, 1999). "Greed Steals From Millionaire". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ James, Caryn (November 18, 1999). "Critic's Notebook; Game Shows, Greedy and Otherwise". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Poniewozik, James (November 17, 1999). "Why Greed Trumps Millionaire". Time. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ McDonough, Kevin (December 8, 1999). "Aretha Hams It Up on Martha Stewart Holiday Special". The Scranton Times-Tribune. New York, New York. United Feature Syndicate. p. 29. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Carter, Bill (December 1, 1999). "TV Notes; Cashing in On Millionaire". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, pp. 219.

- ^ Berman, Marc (November 4, 2019). "20 Years Later: I Still Feel The Need For Greed". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Bierbaum, Tom (November 7, 1999). "Greed good for Fox". Variety. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "National Nielsen Viewership". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. November 10, 1999. p. 82. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nedeff 2018, pp. 307.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (January 12, 2000). "Fox on Sitcoms: Who's Laughing Now?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Alan (January 14, 2000). "And the Winner Is..." Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Alan (March 7, 2000). "What Hath Regis Wrought?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ "National Nielsen Viewership". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. July 19, 2000. p. 237. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baber, David (2008). Television Game Show Hosts: Biographies of 32 Stars. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786445738.

- Bonner, Frances (2003). Ordinary Television: Analyzing Popular TV. SAGE Publications Ltd. ISBN 9780803975705.

- DeMichael, Tom (2009). TV's Greatest Game Shows: Television's Favorite Game Shows from the 50s, 60s, & More!. Marshall Publishing & Promotions, Inc. ISBN 9780981490991.

- Furman, Elina; Furman, Leah (2000). So You'd Like to Win a Million: Facts, Trivia and Hints on Game Show Success. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781466811768.

- Harris, Bob (2006). Prisoner of Trebekistan: A Decade in Jeopardy!. Random House Digital. ISBN 9780307339560.

- Nedeff, Adam (2018). Game Shows FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Pioneers, the Scandals, the Hosts, and the Jackpots. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books. ISBN 9781617136559.

- Terrace, Vincent (2009). Encyclopedia of Television Shows, 1925 Through 2007: F–L · Volume 2. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786433056.

External links

[edit]- Official website at the Wayback Machine

- Greed at IMDb

- 1990s American game shows

- 2000s American game shows

- 1999 American television series debuts

- 2000 American television series endings

- American English-language television shows

- Fox Broadcasting Company game shows

- Television series by 20th Century Fox Television

- Television series by Dick Clark Productions

- Television shows presented by Chuck Woolery